James Geddy Site Historical Report, Block 19 Building 11Originally entitled: "Recommendations for Restoration of the James Geddy Site"

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series—1643

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1994

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RESTORATION OF THE JAMES GEDDY SITEA Duty Officer Report

August 15-17, 1986

Department of Architectural Research

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

A Duty Officer Report

Once a year, the duty officer assignment gives each director and administrative officer at Colonial Williamsburg an opportunity to consider some aspect of the Foundation and report their perspective to the president. Assuming no political upheavals or natural disasters arise to divert the duty officer's attention, he/she has a modest amount of time in which to pursue a topic of personal interest. Like others over the years, I have reported on subjects ranging from the sublime to the myopic. Throughout the process, it has occurred to me that it could be both more enjoyable and probably more useful to include other members of the staff in the weekend effort. By combining efforts, everyone's personality and skills could enliven the process and generate a richer product.

About a month ago, then, I proposed a joint effort to the Architectural Research staff as a voluntary, one-time, two-day project. Reactions were mixed. Some remembered that dissertation proposals would be due or pets possibly ill that weekend, but a surprising majority were inquisitive and cautiously enthusiastic. Part of the attraction of the idea was that it had potential for briefly recreating the kind of experience most of us remembered from architecture school. Popularly called charettes, these efforts involved sizable numbers of classmates working together on design projects, inevitably through the night, driven by the pressure of a classroom deadline and supported by large quantities of eccentric 2 music and inexpensive food. What was needed, we agreed, was a project that could be handled in a relatively brief time, and that offered sufficient complexity to keep each of the seven or eight people working with considerable rigor.

A plan for the physical development of the James Geddy property seemed to fulfill the requirement. The Geddy lot is an important Historic Area site that is open to the public and that has received good-quality research and archaeological excavation, yet has not been fully developed. Both archival and archaeological findings show that, in the period we interpret, the site was more cluttered with buildings than it is today. All those buildings are of the variety we have intensively studied with the Agricultural Buildings Project in recent years, so the duty officer group could bring an unusual amount of background information to the exercise without extensive new research. It was as though we found ourselves at an advanced stage of planning for the Public Hospital or Anderson Forges, with most of the fieldwork done. The Geddy site was accepted as our assignment.

We began the effort on Friday by reviewing the evidence assembled by Vanessa Patrick and by discussing the essential aims of the project. On Saturday morning, the group met again to develop a series of questions and propositions, with help from Mark R. Wenger and honorary architectural historian Cary Carson. We then proceeded to the site to review present conditions and locations of proposed buildings and to continue discussion about the particular character we should create for the Geddy yard. 3 After a selection of a task for each person, we broke for a baseball game (which was won by default then lost with our players supporting the other team) and lunch at Pierce's Barbecue. The charette began in earnest after lunch, broke off briefly late Saturday night, and continued through Sunday until the last person dusted his drawing and covered his board at 9:00 Monday morning, half an hour past the deadline.

During the two days, we retained a number of connections with the outside world. Barbara and Cary Carson spent time working with us and brought lemonade and videos (from which we judiciously selected The Graduate and Paris, Texas). Tom Taylor discussed the conservation implications of our proposal and Mark Wenger stopped to review his plans for Shields Tavern. We paused to check on the rushed progress of archaeology around the Anderson kitchen and occasionally ventured out to original buildings to investigate details. Progressively, we tested Pearce Grove's flexibility in matters of library visitation. On Sunday, the office became something of a storm watch center, with calls coming in from Security, Facilities Maintenance, Collections, HAPO, various exhibition buildings, and Busch Gardens about the course of Hurricane Charlie and its potential impact on the Historic Area. We commented authoritatively on the possibility of frightened horses and flying wheelbarrows. At a particularly dramatic moment, I was called out into the rain with Security to observe two trees that had been nearly severed by beavers and that threatened the west 4 end of the Country Road. This dangerous and intriguing situation was dutifully reported to Gordon Chappell's office. The weekend did indeed remind us all of those ancient charettes. There were the familiar 11 p.m. fears that the project would never be finished, the 2 a.m. rushes of inspiration, the 5 a.m. feelings of hesitant satisfaction balanced by a growing uncertainty about other participants' taste in music. The latter ranged from King Sunny Ade's Nigerian rock to Noel Coward's London nightclub acts, each choice modulating the pace of our work. In the end, we all knew one another a little better, and we completed a project that provides some new options for Colonial Williamsburg.1

We offer these ideas realizing that current economic conditions make their immediate implementation unlikely at best. Moreover, we feel that there are several other interpretive sites that represent a more pressing need for development—especially the creation of a representative black environment at the Carter's Grove quarter and the completion of the domestic and industrial scene on the Anderson property. However, Williamsburg is appropriately and best known for its recreation of entire environments rather than fragments of history outside their physical context. It is important for us to continue to think in 5 these terms as more is learned about the realities of life in eighteenth-century America. Our professional predecessors created beautifully crafted environments that have captured the popular imagination. Without incautiously disparaging those recreations, it is our responsibility to continue applying the best available thought to the historical environment. We have begun at Anderson and Carter's Grove and initial steps have been taken at Peyton Randolph. This report provides recommendations that can be further pursued when the time is right.

E. A. C.

Developing the Geddy Site

One of the reasons that Colonial Williamsburg has become a more interesting, stimulating museum in recent years is that it has directed increased attention to the variety of life in eighteenth-century America. The food prepared in prerevolutionary Virginia was not an undifferentiated mass, defined only by regional boundaries. All black women and men did not dress one way and white people another, The Story of a Patriot notwithstanding. Even in the capital city, approaches to architecture varied tremendously, from palatial to impermanent. It is not the job of a history museum to present every condition that existed in its subject era. For a museum of the Williamsburg sort, however, there is a responsibility to portray honestly a range of conditions and to investigate the nature of relationships between different parts of the community. It is, after all, those relationships that made it a community.

We and our visitors recognize new distinctions among different sites in the Historic Area. Age, functions, and economic status of properties resulted in extremely diverse character, just as it does in a city today. Decorative gardens did exist, for example—the one developed by John Custis probably surpassed any of the ornamental landscapes created here in the 1930s—but there is little evidence that they could be found with the regularity imagined fifty years ago. Increasingly uncomfortable with generalized explanations of how life was back 7 then, interpreters speak in more specific, conditional terms, teaching about how it was in certain situations for certain types of people.

The sharper focus is evident in recent planning for the Geddy complex. A charter document for the site, following the lead of the Foundation's ten-year plan, calls for a clearer, less generic portrait of life on the Geddy property in the late colonial period.2 New attention will be given to changes in the relationships of the craftsman's family to the community, within the family, and between Geddy and his workers. These interpretive goals are analyzed in more detail and specific recommendations set forth in a report prepared for the Program Planning Committee.3 Among the long-range proposals is the reconstruction of the domestic outbuildings that coexisted with the house, and archaeological excavation at the rear of the lot.

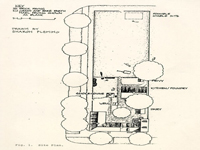

We now know from dendrochronology that the house was built by James Geddy II about 1762, two years after he, age twenty-nine, purchased the property from his mother.4 By about 1770, he was also substantially improving the work area behind the house. An enlarged kitchen-laundry was built, which 8 eventually seems to have housed foundry activities as well as domestic work. A building thought to have been a dairy was constructed between the kitchen and the shop, and a smokehouse was placed beyond an enclosed well, at the end of a walk paved with well bricks. Within the limits of modern excavation, the building furthest removed from the house was a privy hidden behind the kitchen and apparently facing east toward the Norton (now Roscow Cole) property.5

The late colonial developments on the Geddy property are interesting when considered in light of the recent findings at the Peyton Randolph property. Geddy, the successful craftsman and nascent merchant, expressed his advancing position by building a rather impressive new house with an oversized entertaining room at the rear.6 Thereafter, he proceeded to entirely remodel his work yard, combining capital-producing and domestic work functions in a single area. He was not alone in these activities. Some twenty years earlier, political heavyweight Peyton Randolph had chosen to retain the old house he inherited from his father, but had raised it to his own new social standard by adding a wing containing a large and well finished entertaining room. Also on a grander scale, Randolph 9 swept a collection of old structures away from his rear yard and built a series of new work buildings that somewhat paralleled Geddy's assemblage.

Other comparisons are useful, but probably the Anderson complex provides the most relevant contrast. Again, craft and domestic work were intimately integrated in Geddy's yard. Hams were smoked and butter made in buildings adjoining light metal working activities. At some point, casting was done in the same building in which the family's food was cooked. Sales and some production appear to have taken place in the house, probably in space adjoining the principal bedroom. At Anderson, a variety of domestic and capital-producing activities were also located behind the owners house. There, though, the industry was heavier, employing more workers, and the activities were segregated into distinct zones. At the time of the Revolution, the Anderson Kitchen stood midway between a series of forges and the house, and a lateral fence partitioned the domestic yard from the industrial yard. There is some evidence of access to the Anderson shops from both Duke of Gloucester and Francis streets, and both routes were shielded from the house by fences.

As these several examples suggest, the arrangement of the eighteenth-century buildings at the Geddy site both reflects the particular conditions there and is reminiscent of patterns seen elsewhere in town. In order to illustrate the activities that took place there and interpret life and work during Geddy's time, it would be useful to recreate all the components of his 10 property. The house was restored in 1930, and the store was reconstructed in 1954. The present kitchen was reconstructed after a 1965 decision to open the house to the public, but the early Perry, Shaw and Hepburn "local colonial type wellhead" was retained. Excavations in 1966-67 were extremely successful in discovering both architectural and artifactual data, but no further reconstructions have been executed. The following summaries are intended to explain the character and major details of the buildings recommended for reconstruction.

Rear Shed Addition

Before dealing with the structures appropriate for interpretation at the Geddy site, evidence concerning the now-lost shed at the rear of the house should be summarized.

Ever since archaeological investigations in the mid-1960s revealed brick foundations just north of the James Geddy house, it has been speculated that the building had a shed addition between the two cross wings. It is suggested that the shed across the north elevation, which was demolished in 1930 when the house was restored, may have been in fact an early feature. During the 1966-1967 seasons, archaeologists uncovered the remnants of a one-brick thick foundation wall situated about ten feet from the present rear wall of the house. Although the brickwork was eighteenth-century in character, no firm date could be assigned to its several periods of construction other than that they postdated the construction of the main block of the 11 house (dendrochronology date circa 1762). The outline of the house on the Frenchman's Map, showing a U-shaped configuration, suggests that the shed addition had not been constructed by the early 1780s. Were the shed built by this time, the map should have shown the Geddy House quite differently with an elongated L-shape appearance. Therefore, it seems likely that the shed probably dates from the last years of the century. Since this period postdates the occupancy of James Geddy II, it is suggested that the shed not be rebuilt. The question, however, may deserve further inquiry.

Fences

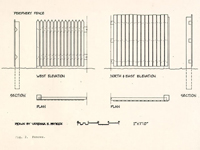

While archaeological evidence for fencing at the Geddy site is fragmentary at best, the enclosure practices of the eighteenth century and the context created by the developments of the 1770s have suggested the following arrangement.

The 1967 excavations revealed a single row of three postholes, dug and backfilled no earlier than about 1755, on the west property line. The enclosure of lots in Williamsburg was required by Virginia law, most particularly by the oft-cited act of 1705, and necessitated by the eternal problem of animal and human encroachment. The practice has been substantiated by archaeological findings, documentation such as the Frenchman's Map and newspaper advertisements, and structural survival in the sense of periodic rebuildings. Thus, it is proposed that fences be constructed at the periphery of the Geddy lot.

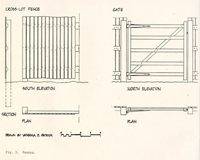

12The west fence is perceived as a product of the 1770s reflecting the general ordering and upgrading of the yard, and perhaps an awareness of the adjacent Palace Green, in sawn and drawn components, wide and regular spacing of pales, and decoratively cut pale tops. The relatively less prominent north fence, with its roughly-sawn components, square and lapped rails and utilitarian field gate, is seen as a retained section of an earlier enclosure. It is quite possible that in the 1770s no physical division existed between the Geddy lot and the lot immediately to the east. Present interpretation of the latter as the Roscow Cole property, however, dictates the definition of the boundary line with a high, close-paled fence like that specified for the northern edge of the Geddy lot.

An east-west line of seven irregularly spaced postholes was uncovered immediately north of the existing well. The redevelopment and expansion of the yard in the 1770s, specifically the construction of a smokehouse, eliminated the need for the fence and consequently it was removed. Thus, apparently no attempt was made to screen the house from the yard or visually segregate domestic and industrial functions as was done at the James Anderson property.

By contrast, the historical character of the rear half of the Geddy lot is essentially unknown. Archaeological investigation has yet to extend beyond the privy site, though available documentation implies the existence of a stable near Nicholson Street. It therefore seems reasonable to interpret the

Fig. 2. Fences.

Fig. 2. Fences.

Fig. 3. Fences

13

northern half of the Geddy lot as undiversified space available for use as anything from a pasture to an industrial trash dump. As the nature of Geddy's work did not result in vast amounts of waste, the yard was presumably less littered than was Anderson's lot or Shields Tavern when forges existed there. A cross-lot fence, envisioned as incorporating pales from the earlier eastwest and replaced west periphery fences, delineates the northern edge of the domestic/industrial yard and completes the enclosure of the northern part of the lot, closely resembling the subdivision of the Wetherburn's Tavern yard.

Fig. 3. Fences

13

northern half of the Geddy lot as undiversified space available for use as anything from a pasture to an industrial trash dump. As the nature of Geddy's work did not result in vast amounts of waste, the yard was presumably less littered than was Anderson's lot or Shields Tavern when forges existed there. A cross-lot fence, envisioned as incorporating pales from the earlier eastwest and replaced west periphery fences, delineates the northern edge of the domestic/industrial yard and completes the enclosure of the northern part of the lot, closely resembling the subdivision of the Wetherburn's Tavern yard.

The dimensions, modes of construction, selection of materials, design, and finish of the proposed fences and gates are based on research undertaken in the Department of Architectural Research during the last three years.7

Paths and Paving

Unlike fences, paths and paving constituted a major archaeological presence at the Geddy site. Most of the paving and paths appeared to date from the period of yard improvement. In-the-ground evidence at Geddy, supported by findings at other Historic Area properties such as the Brush-Everard House and Wetherburn's Tavern, indicate that virtually the entire area bounded by the house, kitchen, and smokehouse should be variously paved in brick, brick rubble and marl. Two axial brick paths 14 emerge from the paving, leading respectively to the smokehouse (with well bricks used as paving) and to the rear of the lot. Branching off from the latter is a partially curvilinear, brick rubble and marl path which served the privy. The paths and paving at the Geddy site clearly express the organization and functioning of a domestic/industrial, urban yard.

Dairy

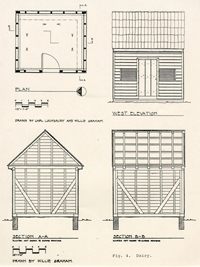

This structure was located midway between the house and the kitchen, immediately north of the Geddy store. The function of the building was not directly indicated by archaeology, but it has been assumed that it was a dairy.8 Several types of information support this theory. According to the ledgers of Humphrey Harwood, there was a dairy on the site by the spring of 1778.9 Agricultural Buildings Project fieldwork has demonstrated that the typical relationship of outbuildings and house in the Chesapeake included placing of the dairy and kitchen closer to the house than other work buildings, generally with the dairy closest of the two. As the functions of most of the buildings represented by excavated foundations are known, this structure is an extremely good candidate for the dairy that Harwood repaired.

The foundations suggested that the building was of frame construction and that its floor was not subterranean like 15 that of the rather famous Grissell Hay (Archibald Blair) dairy. Archaeology revealed little additional information about the character of the building, but documentation reveals that Humphrey Harwood was paid to mend the plaster and to whitewash the dairy—indicating a level of finish observed in dairies recorded in the field. The remainder of the design details are derived from these comparable buildings.

Surviving dairies are generally fairly well finished when compared with other outbuildings on a site. Most are specially ventilated and somewhat well secured. These superior qualities become increasingly evident in the early nineteenth century, however, and we have searched for a balance between the relative high quality of the building type and the lack of specialization evident in most prerevolutionary structures.

As a result, the proposed building is of frame construction, completed in a well-finished manner using mortise-and-tenon joints and sawn material, but with members of slight dimension as found at the Ballard Farm and Cherry Walk dairies (in Somerset County, Maryland, and Essex County respectively). The wall pitch is 7'9", again taken from the same two buildings, and similar to the dimensions called for in a dairy of comparable size in the 1748 Augusta Parish Vestry records. The Geddy dairy is shown with a dirt floor, like the Augusta County example and most recorded in the field. In order to give the dairy a better exterior finish than the smokehouse and privy but inferior to that of the house, sawn and beaded but unplaned weatherboards are

Fig. 4. Dairy.

16

used for all the walls. Two slatted windows of fairly inexpensive construction immediately flank the door, repeating a relationship found in the dairies at Belvedere (Southampton County) and Ballard Farm. The details for the window design are taken from the Belvedere example. For a gable-end window, a sliding shutter of very conventional form, with details taken from a surviving shuttered window in the John Hill barn in Southampton County, is suggested. Maryland Orphans' Court records indicate that side-lapped shingles may have been the most common roofing method in the Chesapeake at this time. Surviving examples are found at Westfalia (Southampton County), Coe Tobacco Barn (Anne Arundel County, Maryland), and a mid eighteenth-century house in Earleville on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. Such roofing is specified because it is appropriate for the indicated quality of construction and it could provide a modest contribution toward the variety of roof coverings that existed in eighteenth-century Williamsburg but now largely lacking. It is not known that all dairies had shelving in the eighteenth century, but most of the extant ones do and there are many documentary references to shelves in dairies from the mid eighteenth century onward. Thus, a small amount of shelving of simple design is included. The details for the shelves and supports are taken from the Elm Grove dairy (Southampton County).

Fig. 4. Dairy.

16

used for all the walls. Two slatted windows of fairly inexpensive construction immediately flank the door, repeating a relationship found in the dairies at Belvedere (Southampton County) and Ballard Farm. The details for the window design are taken from the Belvedere example. For a gable-end window, a sliding shutter of very conventional form, with details taken from a surviving shuttered window in the John Hill barn in Southampton County, is suggested. Maryland Orphans' Court records indicate that side-lapped shingles may have been the most common roofing method in the Chesapeake at this time. Surviving examples are found at Westfalia (Southampton County), Coe Tobacco Barn (Anne Arundel County, Maryland), and a mid eighteenth-century house in Earleville on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. Such roofing is specified because it is appropriate for the indicated quality of construction and it could provide a modest contribution toward the variety of roof coverings that existed in eighteenth-century Williamsburg but now largely lacking. It is not known that all dairies had shelving in the eighteenth century, but most of the extant ones do and there are many documentary references to shelves in dairies from the mid eighteenth century onward. Thus, a small amount of shelving of simple design is included. The details for the shelves and supports are taken from the Elm Grove dairy (Southampton County).

The resulting design is a moderate-size dairy that is well finished, but not to the degree found in most of the dairies

Fig. 5. Dairy.

Fig. 5. Dairy.

Fig. 6. Dairy.

17

reconstructed in the Historic Area. It is our contention that this composition presents a more realistic picture of what a dairy looked like in this context, contrasting somewhat with the more lavishly designed dairies elsewhere in the town.

Fig. 6. Dairy.

17

reconstructed in the Historic Area. It is our contention that this composition presents a more realistic picture of what a dairy looked like in this context, contrasting somewhat with the more lavishly designed dairies elsewhere in the town.

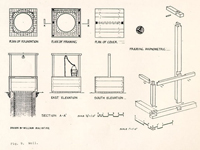

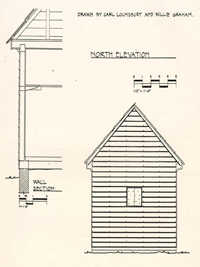

Smokehouse

Archaeological remains left little doubt about the date and function of the structure located at the end of a substantial brick path leading directly north from the house. The nearly square building housed a carefully constructed brick firebox, the ash fill of which contained pieces of creamware and tobacco pipe fragments that indicated the building was used after about 1770.10 Most of the main brick foundation has been robbed, but a sufficient amount survived to show that like the house, kitchen, and supposed dairy, and unlike the privy, the smokehouse was constructed on continuous foundations rather than piers.

Like the design for the dairy, the proposed smokehouse introduces common eighteenth-century technology that is appropriate but now rare in the Historic Area, and it avoids some of the specialized building techniques that are often overemphasized. Perhaps the most evident is the use of sawn and beaded but unplaned weatherboards on the two most prominent sides and riven clapboards on the less visible. Similar concern for facade finish can be seen in other buildings of this scale, such as the Reid smokehouse, which has original flush siding on three

Fig. 7. Smokehouse.

18

sides and contemporary clapboards only on the back (south) facing Francis Street. Studs were sometimes closely set, on 1' centers, to provide added security for eighteenth-century smokehouses, and occasionally for other buildings such as stores that held valuable goods.11 Yet surviving early smokehouses here and elsewhere demonstrate that it was equally common—perhaps more so—to use conventional stud framing with 2' centers. This has been done with the proposed smokehouse, with relatively high-quality mortised studs set flat against the wall covering. It was especially common to reuse salvaged framing in eighteenth-century outbuildings (the Brush-Everard and Reid smokehouses being two among many Williamsburg examples), and the Geddy smokehouse is designed as having old rafters used as studs and plates showing scars of previous use.

Fig. 7. Smokehouse.

18

sides and contemporary clapboards only on the back (south) facing Francis Street. Studs were sometimes closely set, on 1' centers, to provide added security for eighteenth-century smokehouses, and occasionally for other buildings such as stores that held valuable goods.11 Yet surviving early smokehouses here and elsewhere demonstrate that it was equally common—perhaps more so—to use conventional stud framing with 2' centers. This has been done with the proposed smokehouse, with relatively high-quality mortised studs set flat against the wall covering. It was especially common to reuse salvaged framing in eighteenth-century outbuildings (the Brush-Everard and Reid smokehouses being two among many Williamsburg examples), and the Geddy smokehouse is designed as having old rafters used as studs and plates showing scars of previous use.

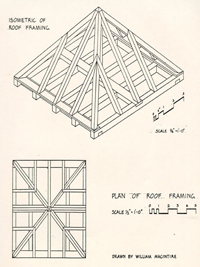

Not all smokehouses had pyramidal roofs, but all that survive in the Historic Area do. We have bowed to this statistic and employed a pyramidal roof. One problem with this type of roof is the manner in which the eaves are framed. The proposed solution, with rafters of two opposite sides resting on board false plates and the other two directly on the plates, is taken from a wrought-nailed smokehouse behind the Holloway House in Port Royal. It is an arrangement which seems particularly well suited to this similarly scaled building slightly less than

Fig. 8. Smokehouse.

19

square in plan. As with virtually all Williamsburg smokehouses, riven sticks for hanging meat can be set directly in the conventional building frames. No specialized structure for hanging vast quantities of meat has been used.

Fig. 8. Smokehouse.

19

square in plan. As with virtually all Williamsburg smokehouses, riven sticks for hanging meat can be set directly in the conventional building frames. No specialized structure for hanging vast quantities of meat has been used.

Well

In a work space of combined industrial and domestic functions such as the Geddy yard, water was in constant demand. The final relocation of Geddy's well placed it in a central location, convenient to both the workshop and the house. The current reconstruction of the well cover caps the well with an attractive, pyramidal roofed, lattice-work structure that has eighteenth century precedent in Williamsburg, but which would be most appropriate for a formal garden setting rather than a work space. The most common well types, working wells, are currently not found at all in the Historic Area. The Geddy yard provides an excellent opportunity to place such a well in a working environment.

The archaeological investigations on the Geddy lot revealed useful information about the well. A square, single-course foundation of bricks surmounting the round brick well shaft suggests a box cover, and provides its dimensions, at least in plan. The structure we have designed is informed by several sources. From Benjamin Latrobe's drawings to Susan Nash's surveys to examples found in recent architectural surveys of Virginia, the form changes little until twentieth-century 20 technology made it obsolete.12 It consists of a simple box-like cover. In spite of the persistence of the form, it is reasonable to assume the construction of the eighteenth-century type varied in some details from those built later. In the absence of a surviving example, the construction of the Geddy well is drawn from such precedents as small structures like the Pruden milk house in Isle of Wight County, and carpenter-built furniture such as chests and boxes. Thus we have used inexpensive, half-lapped joinery, that is, elements simply nailed together rather than mortised and tenoned. The well cover may have been absent or rarely used in the eighteenth century, but it is presently needed for safety reasons, and so is built with appropriate technology. Either winches or pulleys were used to draw up water. A pulley is suggested as the most common type. Simple pulleys such as the one shown here are found in Diderot, and in paintings from a variety of European countries.13 The bucket depicted here is drawn from an example retrieved from a well at Wetherburns' Tavern.14

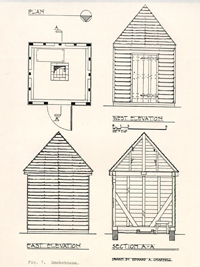

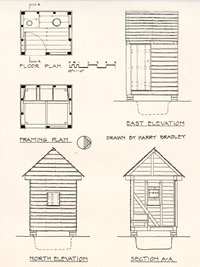

Privy

The site for the privy has been clearly determined by archaeology. It is located in the northeast corner of the lot 12' north of the kitchen and 6' west of the eastern boundary between colonial lots 161 and 162. The only existing documentary information for a privy is an intriguing 1760 reference found in Deed Book 6 of the York County records. It states that the tenants of the neighboring rental property (now Roscow Cole) shall have "free use of the necessary house and well belonging to the said lot . . . . [i.e. Geddy]."15

Archaeology has also revealed several other important facts. The size of the pit is 3'0" by 3'11" and only about 1' 6" deep. One brick pier and fragments of a second were found. Unfortunately, no evidence for the remaining two was uncovered, but their location can be interpolated. With this information, a foundation size of 5' 0" by 5'6" is the result. Fragments of a brick rubble and oyster shell walk leading to the eastern side of the privy revealed the location of the door, reinforcing the impression that this privy and perhaps a predecessor were used by occupants of the Norton property as well as the Geddy complex.16

All other design decisions were based on fieldwork at extant eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Tidewater Virginia and Maryland privies and consideration of the common

Fig. 10. Privy.

22

relationships in the levels of finishes for privies and other outbuildings on a single site. The primary source is the Whaley privy in Berlin, Worcester County, Maryland. It was used to determine overall form, location of openings, and the relationship between the door, window, and the child and adult holes (with the adult hole beside the window, the child's in front of the door). It also reveals the use of riven clapboards on the exterior and exposed framing on the interior. Other privies with unfinished interiors recorded by the Agricultural Buildings Project include those at the Coke-Garrett House and Burley Manor, the latter also in Berlin. The rather grand privy at Westover indicates that some sort of wooden backboard was not a requisite component, although such a feature is most often found in better finished eighteenth-century examples like those at Brandon and Bowman's Folly. The relatively low height for the structure is taken from the Myrick privy in Southampton County. The rather modest level of finish, exemplified by the lack of corner boards and baseboards, is consistent with the secluded location of the privy and the assumption that it would have been one of the least finished structures on the site. The omission of these features is common, but not inevitable among Chesapeake buildings.

Fig. 10. Privy.

22

relationships in the levels of finishes for privies and other outbuildings on a single site. The primary source is the Whaley privy in Berlin, Worcester County, Maryland. It was used to determine overall form, location of openings, and the relationship between the door, window, and the child and adult holes (with the adult hole beside the window, the child's in front of the door). It also reveals the use of riven clapboards on the exterior and exposed framing on the interior. Other privies with unfinished interiors recorded by the Agricultural Buildings Project include those at the Coke-Garrett House and Burley Manor, the latter also in Berlin. The rather grand privy at Westover indicates that some sort of wooden backboard was not a requisite component, although such a feature is most often found in better finished eighteenth-century examples like those at Brandon and Bowman's Folly. The relatively low height for the structure is taken from the Myrick privy in Southampton County. The rather modest level of finish, exemplified by the lack of corner boards and baseboards, is consistent with the secluded location of the privy and the assumption that it would have been one of the least finished structures on the site. The omission of these features is common, but not inevitable among Chesapeake buildings.

Kitchen

The present kitchen, reconstructed in 1966, is a reasonable interpretation of its late colonial predecessor. Its 23 appearance has been made much more believable by the recent change from a polychrome paint scheme to whitewash over a Spanish brown primer. We see no problem in retaining the kitchen.

Future Archaeology

While the domestic/industrial yard adjacent to the Geddy house has received considerable archaeological attention, the rear or northern half of the lot remains largely unexplored. Careful excavation offers the most reliable, and perhaps only, means by which certain important questions about the Geddy site may be answered. The existence of a stable is suggested by the written record, either ignored or denied by the graphic record, and complicated by ownership changes in the neighboring lot. Was there a stable on the Geddy lot and, if so, where and when was it constructed? Given the known character of the property, additional questions arise. Were other structures, including fences, present at any time and what functions did they serve? To what extent was the rear portion of the lot used for gardens, domestic/industrial storage or refuse disposal, animal accommodations, or vehicular access to the area closer to the house? A thorough archaeological investigation of the northern half of the Geddy site is thus recommended as useful in achieving an accurate, comprehensive interpretation of the property.

A View From the Green

Our generation at Colonial Williamsburg finds itself in an unusual and interesting situation. We have the pleasure of working with a sizable part of an eighteenth-century town that, over the last fifty-five years, has been largely restored to what the contemporary scholarship of the day indicated was its colonial appearance. There are still some important missing pieces—slave housing, a major gentry service complex at Peyton Randolph, the Custis garden, the remaining parts of James Anderson's work yard, a few early houses along Francis and Nicholson streets, the market house, and others—but by and large the town has been mostly rebuilt.

The last fifteen years have also seen a thorough reevaluation of what life was like in the Chesapeake colonies, with some sobering implications for what Colonial Williamsburg has shown and taught. Six years ago, visitors to the Governor's Palace still heard that slaves were required to whistle as they delivered dinner to ensure that the food was not sampled. Interpretations have improved dramatically, and new reconstructions—the Public Hospital, Greenhow Store, Anderson, and at Carter's Grove—have followed a more complex approach to investigating the past. Yet, that other 98% of the restored town remains unchanged, with all its fretted and espaliered richness. Much of it, of course, is well documented and convincing. Other aspects, like decorative water pumps at the center of little Versailles gardens, are incontestably the products of an earlier 25 twentieth-century view of history, rather than solid recreations of what was here.

The practical and intellectual problem is that much of this cannot (and possibly should not) be changed. No one seems to feel that every possible step should be taken to erase twentieth-century amenities from Williamsburg. Nevertheless, few if any are prepared to accept the Historic Area as primarily a Colonial Revival creation immune to growth or alteration. In a recent statement of criteria for architectural change, the Program Planning Committee declined to address the presence of the Colonial Revival as a factor of significance. So the question of how to treat the Historic Area is, in its broadest terms, an extremely difficult one. Each property must be dealt with on its own merits and general policy informing these decisions remains elusive.

In pursuing a policy, two concepts may be useful. First, unless precluded by concerns for preservation of early fabric (as at the Benjamin Powell site), exhibition sites should physically represent the period to which they are interpreted. For example, inauthentic foundation shrubbery would be removed from Wetherburn's Tavern but the evocative Colonial Revival garden behind the Orlando Jones House might remain. Second, special consideration should be given to areas of crucial historical and visual importance. Thus, the Orlando Jones garden should be preserved not only because it does not disrupt an interpreted site, but also because it does not intrude into an 26 essential public or domestic scene. All parts of the Historic Area are important, and the discovery of nearly hidden but carefully considered features is part of most people's delight with the place. Yet there are areas of high visibility that are pivotal in our portrayal of the eighteenth-century town. These areas too, over time, should be nudged toward an appearance that accurately reflects eighteenth-century conditions.

Palace Green is a prominent example. It is a vital component of Francis Nicholson's grand plan for Williamsburg and retains one of the strongest neighborhood identities in the restored town. In the eighteenth century Palace Green was a more complex, less homogeneous place than it appears now, because of the governors' residence and some gentry and upper middle-class houses standing side by side with structures with little or no pretensions. At the intersection with Duke of Gloucester Street, the Custis family maintained a tenement of little apparent sophistication. From immediately behind the Wythe property, a lead manufacturing operation made itself evident to visitors on the Green. Nearby, the old theater was used as a makeshift courthouse, occasionally attracting loud and unruly crowds. In their yard beside the Green, the Geddy family and workers practiced their metalworking trades, cooked, washed, and cured hog meat in clear view of the colony's most genteel urban space.

While the vigorous presence of folk culture can not be recreated at every tenement and lead manufactory in Williamsburg, 27 it is important for us to deal with the known realities of significant landscapes, like that which existed as Palace Green. The juxtaposition of formal edifices and commonplace activities was one of the principal characteristics of life in the eighteenth century. The recreation of well-chosen components such as the Geddy group, can ensure a liveliness and greater realism for the Historic Area in general, and, in addition, inspire expressive interpretation of individual sites.